Architecture & Design

There are 10 types of people: those who understand binary, and those who do not.

--anonymous

In landscape architecture there is an evolutionary design technique using desire lines .

Problem : Where to build, and how wide to build, outdoor pathways?

Solution : Wait for a year and observe the paths people naturally walk, and traffic volume. Create permanent paths along these desire lines, as wide as appropriate. Design is pulled from demand rather than speculatively pushed.

Although challenging to apply in product design, this is one source of inspiration in lean or agile design–a kind of emergent design .1

There is probably a market for a great book on Agile Large-Scale Design ; this is not it. This is not a treatise on technical design; it offers a few behavior-oriented tips related to design and large-scale development with agility, with a few noteworthy technically oriented tips–some analogous to desire lines. Some tips reflect lean software principles such as decide at the last responsible moment . Some reflect agile principles such as the most efficient and effective method of conveying information is face-to-face conversation . And many suggestions reinforce the ninth agile principle: Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility .

Thinking About Design

Think ‘gardening’ over ‘architecting’—Create a culture of living, growing design

We considered calling this section simply Design , but decided on Design & Architecture because of the extant belief that the software code, design, and architecture are separate things, and therefore that ‘architecting’ and programming are separate.2

The word architecture has at least two broad implications in common parlance in software development:

- (noun ) the large-scale static and dynamic themes and patterns

- there is also intended architecture (speculated, wished for) versus actual architecture –which may not be wished for

- (verb ) the creation and definition of the intended architecture, as in ‘architecting’ or, “When will you do the architecture?”

- it is performed once near the start, often in documents

- it overlaps with requirements analysis

The term was borrowed from building architects. It turns out to be a weak analogy3 with interesting side effects for software development. Buildings are hard and so in that domain the act of architecting is only done once before construction–at least, these days–and then the building or architecture is more or less permanently fixed. Note also that the architects are different from the construction workers. But software is not a building, software is soft , and programming is not a construction process ; “software architecture” is merely one imperfect analogy from a large list of metaphors that could be chosen.

What other metaphors apply? In the oft cited paper “What is Software Design?” by Jack Reeves, the author observes

… the only software documentation that actually seems to satisfy the criteria of an engineering design is the source code

I (Craig here) wrote a book on software analysis, design, modeling, patterns, and architecture. I mention this not to suggest I’m any good (I have average development skills), but I’m probably not a ‘hacker’ (in the bad sense); I appreciate the art and value of modeling and ‘architecting.’ However, having also worked as a hands-on programmer since the 1970s, I recognize that diagrams and documents are not the real design but rather that the source code is the real design . To reiterate, “…the only software documentation that actually seems to satisfy the criteria of an engineering design is the source code.”

The source code (in C, C++, …) is the real blueprint. And near-unique to software, construction or building is almost free and instantaneous.4 Consequently, many do not see it for what it is: Building (construction) is the compile and link step. It is no coincidence that in development tools, the menu option to perform compile and link is labeled Build .

Scenario : In the early days of ProductX, suppose there were speculative but high-quality design documents for the large-scale elements, idioms, and interactions of the intended architecture, and suppose somehow the real design (the source code) well reflects these intentions. Seven years pass, all the original programmers are no longer programming, and 300 new developers have been hired who are poorly skilled and do not really know or care about the original large-scale design ideas. Imagine they have added 9.5 million lines of code–9.5 MLOC, suppose it is 95 percent of the total code–and it is a mess.

Where is the real architecture–good or bad, intentional or accidental? Is it in documents being maintained (or not) by an architecture group, or is it in the ten MLOC of C and C++ within tens of thousands of files? Obviously the latter–the source code is the real design and its sum reflects the true large-scale design or architecture. The architecture is what is , not what one wishes it to be. The ‘architecture’ in a software system is not necessarily any good or intentional.

First observation –The sum of all the source code is the true design blueprint or software architecture.

The software design/code improves or degrades day by day, with every line of code added or changed by the developers. The software architecture is not a static thing. Software is like a living thing, more like a plant or garden than a building, and the living design or architecture is growing better or worse day by day.

Second observation –The real software architecture evolves (better or worse) every day of the product, as people do programming .

The analogy to gardening, parks, and plants is salubrious. For example, there is the noun and verb landscape architecture –it is normal and skillful to consider and ‘architect’ the big picture when planning a big garden or park. And yet people do not leave it at that. Because of the visible nature of a park, and because plants grow, it is crystal clear that the actual landscape architecture will quickly devolve into a jungle of weeds without constant gardening or pruning by hands-on master gardeners mindful of the park’s original or evolving vision. We have a friend who works as a landscape architect for golf courses. He sees with his own eyes the details of the real, living course while it is being created, walking around it and playing golf–in touch with the reality of what is.

This shift from the metaphor of architecting and building software to growing it like a plant has influenced many people reflecting on successful development. For example, Frederick Brooks, in his famous article, No Silver Bullet , shares his shift in understanding:

The building metaphor has outlived its usefulness… If, as I believe, the conceptual structures we construct today are too complicated to be accurately specified in advance, and too complex to be built faultlessly, then we must take a radically different approach… The secret is that it is grown, not built … Harlan Mills proposed that any software system should be grown by incremental development… Nothing in the past decade has so radically changed my own practice, or its effectiveness… (emphasis added)

Third observation –The real living architecture needs to be grown every day through acts of programming by master programmers .

Fourth observation –A software architect who is not in touch with the evolving source code of the product is out of touch with reality .

Fifth observation –Every programmer is some kind of architect–whether wanted or not. Every act of programming is some kind of architectural act–good or bad, small or large, intended or not .

What does this have to do with large-scale development and agility?

In a small product group with 20 people, people well understand the above, and there is rarely an institutionalized false dichotomy or division between architecting and programming. Also, if there is an official ‘architect,’ then this person is typically a master programmer, close to the code. But in a large product group with 600 people in a colossal enterprise, there is a common mental-model mistake–that design or architecting is definitely separate from the code and act of programming. Consequently, it is not uncommon to find an official architecture and/or systems-engineering group, an institutionalized ‘architecting’ step by them (before programming), and its members are not daily hands-on developers or (at least, no more) world-class code craftsman.

This architecture group (or systems engineering group) generally contains well-intentioned and bright people. But (there had to be a but here), in a traditional organization they slowly lose touch with the reality of the source code and become what are called PowerPoint architects, ivory-tower architects, or architecture astronauts– so high up and abstracted from the code (real system) that they are in outer space.

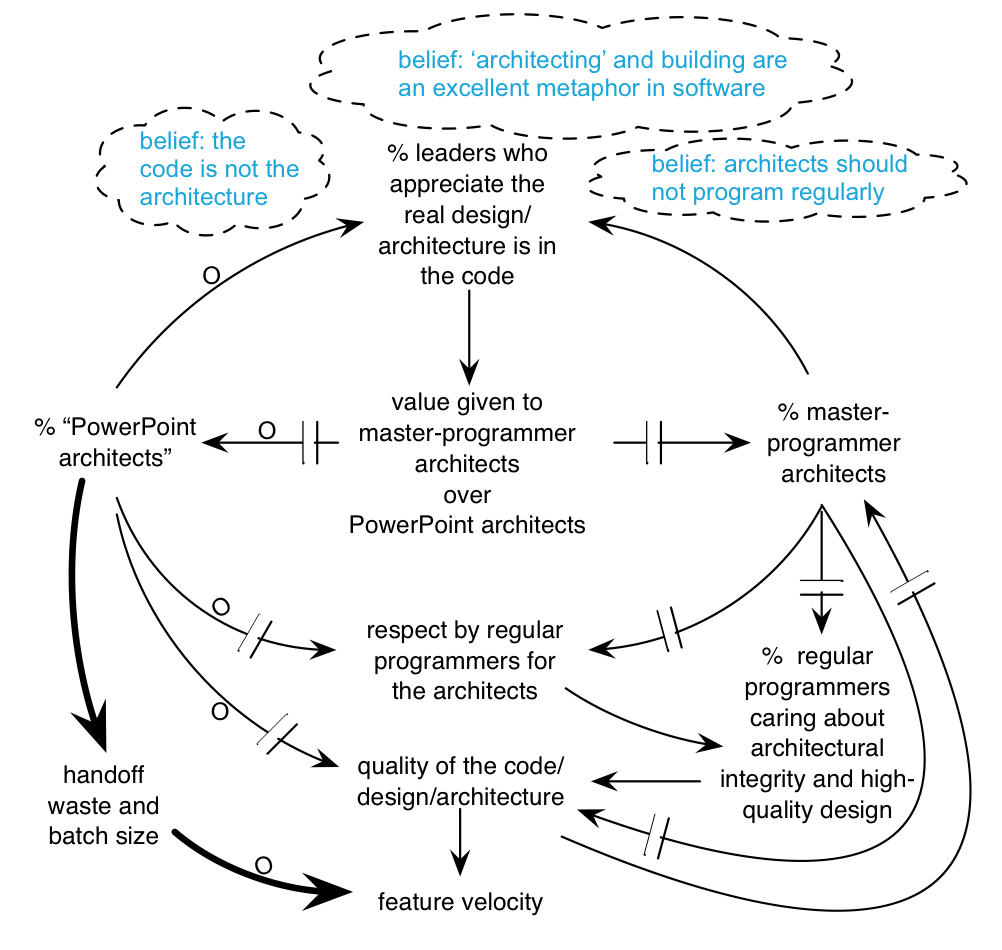

The repercussions? In a large product group with (1) the mental model that the weak metaphor of architecting and building a software system like a building is believed to be a good metaphor; (2) the lack of realization that the true architecture is in the sum of the source code; and, (3) a cadre of architecture astronauts, all this leads ironically to a degrading architecture over time. Why? Some of the dynamics in play are shown in the system dynamics model in the figure below. Note the several positive feedback loops that can reinforce degradation or improvement over time.

Also, what happens to the code–the real design–in a group with the following cultural value and message?… There is the architecture group over there; you regular programmers are not architects . The programmers naturally feel that the architecture is not their responsibility, and degradation of architectural integrity continues.

If the system dynamic increases the influence of PowerPoint architects, the outcome is that they have decreasing influence over time, since they are not in touch with the reality of the code. Eventually, they lose complete touch and end up writing documents for each other or for business stakeholders. The real accidental-architects (the programmers) basically ignore them.

We once had a discussion with a skilled programmer who wrote device drivers for network processors, part of a very large product. He was concerned because the ivory-tower architects–who were located two floors up, literally in another tower –had selected a new network processor that would require a complete rewrite of all the drivers–estimated to be at least nine months of programming work. And that did not even account for testing and resolution of unexpected behavior from a new processor family. Having written drivers for many processors, the developer was an expert on the subject, and he agreed that the new processor was better–at least on paper. However, he also knew that upgrading the existing processor to a newer model in the same family would achieve almost the same benefits, and with zero effort to change any drivers. He seriously doubted that the ivory-tower architects were aware of the effort and impact on the software development–none of them had talked with him; nor in fact did they spend time talking with any real hands-on programmers.

Architectural foundation? –“It is important to have the architectural foundation before you implement anything else, otherwise you can’t have an architectural foundation.” This false dichotomy idea stems from the building metaphor, as though a software system were made of concrete rather than soft ware–as though major system elements could not be improved through learning cycles and refactoring. Coincidentally, while we were writing this section, we had a beer at a pub in Oxford, England, with Alistair Cockburn (an agile thought leader) who told us that he and his wife wanted a basement added to their existing house. The builders lifted the entire house, dug a basement beneath it, and put the house back on top. It’s amazing what ‘architectural’ foundational changes are possible if one thinks outside the box–and software is a lot softer than a house.

Certainly it is important to have great architecture. It is so important that every act of agile modeling and programming for the life of the system should be treated as an architectural act. We all agree that good architecture is important; the question is, what is a skillful way to achieve it ? Most of the tips in this section offer suggestions for how to create and maintain a great ‘foundation’ that is not based on the building metaphor or sequential life cycle.

No false dichotomy: Upfront modeling is fine, documents describing the intended architecture are fine, and so forth. But the architecture, and our learning about it, can improve . Speculative software architecture should be made concrete and not of concrete.

Agile architecture comes from the behavior of agile architecting —hands-on master-programmer architects, a culture of excellence in code, an emphasis on pair-programming coaching for high-quality code/design, agile modeling design workshops, test-driven development and refactoring, and other hands-on-the-code behaviors.

Behavior-Oriented Tips

Design workshops with agile modeling

A requirements workshop brings together customers and developers in face-to-face facilitated workshops. They are tremendously helpful, not only to better learn user needs but–key point–to create a common understanding among all participants.

These same benefits apply to a design workshop . In contrast to a requirements workshop it does not include customers, but it does include all members of the feature team–the people with skill in programming, system engineering, architecture, testing, UI design, database design, and so forth.

When?– Consider holding design workshops at the start of building each new item (for example, three design workshops for each of three items in an iteration), and just-in-time whenever else the team finds agile modeling at the walls useful.

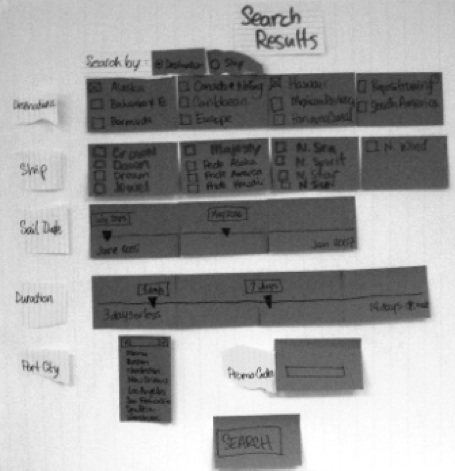

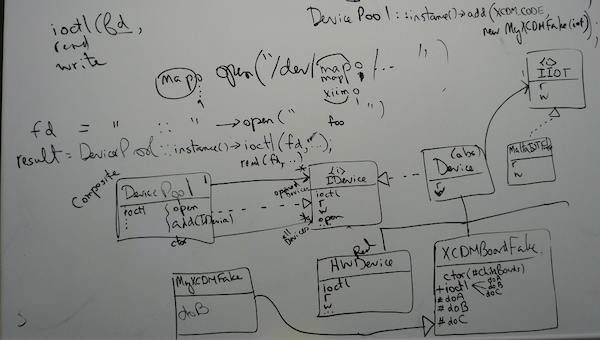

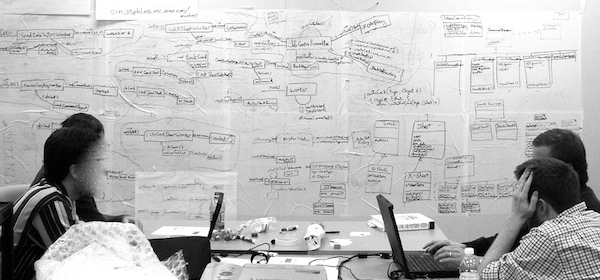

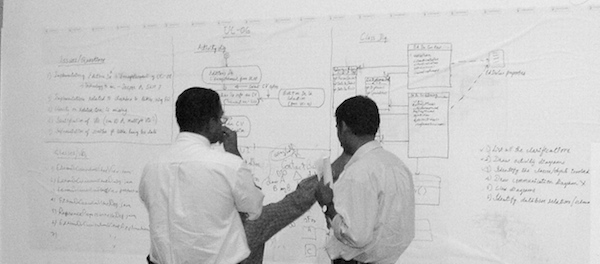

Model what?– During a design workshop, feature teams focus on modeling related to their upcoming goals, or to the overall system architecture–or both. All kinds of design modeling occur: low-fidelity UI modeling with sticky notes or in prototyping tools, algorithm modeling with UML activity diagrams, object-oriented software design modeling usually sketched in UML-ish notation, and database modeling likewise.

This is not a requirements workshop; by the time your teams come together in design workshops, you should more or less understand the requirements under design. Naturally, there are always requirements clarifications or issues raised during a design workshop.

Vast ‘whiteboards’ –A design workshop requires massive ‘whiteboard’ space. Standard whiteboards are possible but not usually sufficient–and in fact are often an impediment, because modeling is best done on vast open wall spaces without borders . You will want to cover virtually all wall space with ‘whiteboard’ material, usually about two meters high.

We have noticed over the years as we facilitate agile design workshops that there is a linear correlation between their effectiveness and the amount of whiteboard space.

At office supply stores or sites you can buy “cling sheet” or “sticky sheet” whiteboard-like materials that either cling to the wall by static cling or by adhesive.5 You can also buy “whiteboard wallpaper”–an excellent solution for floor-to-ceiling ubiquitous whiteboards. One organization we coached bought cheap bathroom waterproofing plastic wall panels that worked great as whiteboards; they covered the entire room with them. Once these ‘whiteboard’ areas are formed, they can be left up permanently.

The best modeling tool? –I (Craig here) wrote Applying UML and Patterns . As a result, people who know this sometimes ask me what CASE or “model-driven development” (MDD ) or “model-driven architecture” (MDA ) UML tool I use. Or, if I’m facilitating a design workshop, they might ask what CASE/MDD/MDA tool to set up. They are usually amused when I answer, “The best modeling tool that I know of is a fresh black marker pen, a group of people, and a giant whiteboard area. Sketching UML on the wall is great.”

UML software tools are sometimes useful, and there are situations when we will recommend one. For example, they can be useful to automatically and quickly reverse engineer the code base into a set of diagrams that help one see the big picture. But for forward engineering or code generation, they can–given today’s technical limitations–inhibit some important goals, explored soon.6

This collaborative sketching, simple-tool, and decades-old approach falls under the category of what has been agile modeling.

Leaving aside the many tips and techniques of agile modeling, why model in a workshop?

model to have a conversation

This is a reiteration of The First Law of Diagramming explored in the Systems Thinking:

The primary value in diagrams is in the discussion while diagramming–we model to have a conversation.

We encourage teams not to model together at the walls to specify , butto have a conversation –to explore and discuss together and come to a shared understanding about designs and requirements, to help develop a shared mental model, and learn together. No doubt some of the object-oriented UML models or UI prototypes on the walls will end up successfully realized in code, but that is a side benefit of taking the time to think, talk through, and sketch ideas together.

Models are not specifications –Any model created before code is just a guess (and a context for a conversation), not the real design, which only exists in the source code. In agile modeling it is rightly viewed that diagram sketches and text are inspiration, not specification . The best design documentation (for maintenance purposes) is created after code is complete, using the SAD workshop technique described in.

All models are ‘wrong,’ and that’s OK –People model to have a conversation, for inspiration and growing understanding, especially shared understanding. It is natural that models are ‘wrong’–that design evolves as people hit the reality of programming and learn.

Wiki photos –Teams often take photos of wall sketches and put them at their product wiki site.

Design workshops and architectural integrity –On a tiny six-person software project, it is possible to get by without structured group modeling workshops. As we scale to larger teams and projects, the value of group modeling to build shared understanding of design ideas is increasingly appreciated. Architectural integrity is a key issue in scaling systems; maintaining that integrity really boils down to the design ideas in the minds of programmers–are they converging or diverging? Design workshops help develop converging design ideas and architectural integrity.

Waste reduction, teaching –In lean thinking, there is a focus on improving through reducing the wastes, and lean product development focuses on outlearning the competition. Design workshops support these goals:

- Workshops reduce the wastes of handoff anddelay . Rather than a technical designer or architect creating a design document and sending it to developers,7 rather than a person getting feedback on design ideas through indirect document review, in a design workshop these parties come together and communicate and give feedback directly and immediately. This also supports agile principle six–The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation .

- They reduce the waste of information scatter, as people are in close conversation, discussing details together at a whiteboard.

- They reduce the waste of underutilized people, as people learn from each other and thus grow in capability.

- They increase knowledge, both in terms of teaching others and in terms of generating new ideas through the cross-pollination effect of a group of seven people creatively exploring together.

- In a lean organization, managers and seniors are also teachers. Design workshops provide an excellent forum for leaders to coach others in design skills and architectural themes.

- They encourage simple visual management.

- They encourage the lean principles of building consensus and cross-functional integration.

Simple tools, flow, participation –Humans are not built visually and biomechanically to stare at tiny computer screens and move a mouse around. People are built for cave art. Try to have a collaborative, creative five-hour design workshop with seven people around a computer display . Death-by-meeting. Yet invite those same people to vast ‘whiteboard’ areas, give them marker pens, and good things will happen (especially if they have had some workshop and agile modeling coaching). These simple enjoyable tools–especially the vast whiteboard space–encourage creative flow and participation . That’s important.

Simple UML –Since humans grasp information well in graphical forms (“bubbles and arrows” rather than just text), we encourage people to become comfortable with some basics of a few UML notations, including activity, class, and communication diagrams. But detailed notation is quite unimportant–model to have a conversation, not to specify.

How long? –Two hours to two days. As with all events in Scrum, timebox the workshop beforehand so teams know the limit.

Just-in-Time (JIT) modeling; vary the abstraction level

In addition to larger and longer whole-team design workshops, consider this scenario: Someone (or a pair) is programming and becomes blocked. They need a different perspective. We often see such a pair grab a small piece of paper and sketch, but if they were working in a team room and the walls were covered with some kind of vast ‘whiteboard,’ this person, more effectively, could stand up, turn around, invite a colleague, and start sketching and discussing for a few minutes or a few hours. JIT modeling .

Notice that this allows people to vary their abstraction level frequently and easily–from code to models to code. A common false dichotomy is that the only time for high-level abstraction-thinking about the system is during a pre-programming phase. Not so. With the practice of agile modeling and a supportive environment, people can flip levels all the time.

Design workshops each iteration

Plan for and hold at least one design workshop each iteration, at least near the start–and possibly more for each item undertaken in the iteration. Timeboxed in the range of two hours to two days. The focus will usually be for features of the iteration, though sometimes farther-horizon modeling makes sense. A team may hold a small design workshop before the first item goal, then another workshop four days later before the second goal, and so forth.

For very young systems, sometimes the design is so unclear in early iterations that the following is necessary: Suppose it is the last week of the iteration. After the Product Backlog Refinement workshop (it usually occurs mid-iteration and looks forward to future iterations), also hold a design workshop related to the likely goals of the next iteration, or beyond–if large-scale architectural issues need to be explored. This will clarify planning during the Sprint Planning on the first day of the next iteration.

Design workshops in the team rooms

It is useful if the walls of each team room are covered in vast ‘whiteboard’ material so that design workshops can be held there. When developers sit to program, they can easily look at the walls for inspiration, or get up for quick modeling conversations, and easily do JIT modeling.

Multi-team design workshops for broader design issues

How to work on cross-team system-level design and architecture issues? How to work on cross-system “product line” design issues?

More broadly, suppose…

- several feature teams work on a common component or framework, since feature teams work cross-component and synchronize at the code level

- one team or product group takes on a common shared goal (such as a common feature or infrastructure) that will eventually be used by other groups

- teams are (suboptimally) organized as component teams rather than feature teams, and one customer feature spans several component teams

- representatives from many teams want to get together to explore and decide on system-level architectural design issues

In any of these cases, it is useful if the teams or team representatives–within one product or across products–hold a multi-team design workshop together. This is not a PowerPoint presentation while sitting around a table; this is people (from different teams) at the walls sketching together–agile modeling. They all work together on vast whiteboard spaces, or sub-groups may work on separate walls and visit each other’s work to learn and give feedback. Some teams may send a representative to the other team (wall) during the workshop.

Who attends? This is attended by regular feature team members, technical leaders involved in the hands-on programming–and not by PowerPoint or astronaut architects.

When? Consider a product-level multi-team design workshop (for system-level ‘architectural’ issues) at least once every few iterations.

After a multi-team design workshop, participants return to their home teams. Later, during the repeating single-team design workshops, the returning people who attended the multi-team workshop share the decisions made cross teams, and help the single team express these large-scale architectural decisions in their agile-modeling sketches on the wall–and then in the code through pair-programming coaching. So, there is a transmission of broad-design ideas and decisions from the multi-team design level to the team design level.

Note the emphasis on a culture of ongoing human infection and mentoring, rather than “documenting the architecture” and handing off The Architecture Document.

A multi-team design workshop is a community of practice activity–in this case, for a design or architecture CoP. So, who organizes regular multi-team design workshops? It may be a design CoP facilitator .

Another reason to have multiple teams in a multi-team design workshop is described next…

Technical leaders teach at workshops

Problem: lack of general design skill and of specific knowledge (about the architecture, other components, …). Education is a remedy. In lean, master-engineer managers are also teachers, coaching people in engineering. During design workshops, technical leaders, managers, and programmer-architects help their own ‘home’ team or help other teams. They may spend many hours with one team at the walls, educating to deepen people’s skills and to establish and maintain architectural integrity.

Architects and system engineers are regular (feature) team members

The prior suggestions related to multi-team design workshops could give the impression that there is a separate architecture group or system engineering group–a misunderstanding. Teams in Scrum are cross-functional and do all the work necessary to deliver customer solutions–and that includes architecture and systems engineering. So, as a product group transitions to agile development, they dissolve the prior separate single-functions groups (such as an architecture group) and the members join regular Scrum feature teams, participating in the hands-on engineering–and, especially, mentoring during design workshops, multi-team design workshops, pair programming, and agile SAD workshops.

“Member of the team” does not mean a ‘fake’ team member–a person who receives work requests from one or more teams, does ‘their’ tasks separately, and gives ‘their’ completed work back.

Question all early architectural decisions as final

So, you do some early architectural analysis and decide that the programming language should be chosen early, suppose C++. Encourage everyone to question and challenge all these assumptions and decisions, and to find ways to apply the lean thinking principle of decide as late as possible or defer commitment . For example, do fast prototyping in Ruby to first learn more. We know of one product that started with C++ for four iterations, and then switched to Java with relatively little effort.

Don’t comform to outdated architectural decisions

All developers have had the experience, “Well, this is pretty awkward, but I’ll fit what I’m doing into the existing approach because it isn’t worth the effort to change things.” Effort includes technical effort and the political effort to convince the ivory tower of architects. On little systems, a culture of conformance over challenge-and-improve only creates moderate weakness because the technical debt is not so large…yet. In large systems–or systems that are destined to become large–this technical debt becomes a monstrous boat anchor that anchors the entire product group…forever. It is especially in the early years when the big and growing product is still ‘small’ that you want to encourage lots of challenge to the original architectural decisions and promote deep-change ideas (achieved with refactoring and continuous integration) before the boat anchor starts to drag your product under water.

Avoid architecture astronauts (PowerPoint architects)

In small organizations there is little money or time for “architecture astronauts” or “PowerPoint architects” or ivory-tower architects who draw and talk about systems at abstract levels, but cannot code them and are out of touch with the reality of the code. In large product groups, this type does appear. In the book that won the 2005 Jolt Productivity Award (for contribution to software development), the author comments:

These are the people I call Architecture Astronauts. It’s very hard to get them to write code or design programs, because they won’t stop thinking about the architecture… They tend to work for really big companies that can afford to have lots of unproductive people with really advanced degrees that don’t contribute to the bottom line.

In lean thinking, there is an emphasis on manager-teachers who are masters of the work and who mentor others, and on working as a hands-on engineer for years. Large product development following lean practices encourages a chief engineer with up-to-date “towering technical competence” as well as business vision. Architects who look down upon “only coding” as something they have evolved beyond have no place in a lean and agile organization.

As discussed in the “gardening over architecting” tip, several dysfunctions arise from the beliefs that the code is not the real design and that the technical leaders do not have to be in touch with the reality of the code.

Plus, always-evolving programming-designing practices and tools (test-driven development (TDD), refactoring, …) should influence the thinking of the technical leadership. For example, really comprehending the subtlety and influence of TDD or refactoring takes long hands-on practice. Without that insight, an ‘architect’ is ignorant of certain forces, dynamics, or action tools in developing systems.

You want master-programmer architects, who are in touch with the code, and who are active developers and mentors–probably through pair programming and design workshops.

This tip does not imply that technical leaders only sit and program; naturally, they decide and communicate major design decisions (perhaps in multi-team design workshops) and stay in touch with the intersection of market forces and the architecture [Hohmann03].

As explored in the causal model in See causal loop diagram of some dynamics related to the ‘architecting’ metaphor., a “PowerPoint architect” is often physically and socially disconnected from the real work and the real workers–inconsistent with the lean Go See principle.

Very early, develop a walking skeleton with tracer code

Old and wise advice is to develop a walking skeleton of a system–be it large or small–very early, to learn about an appropriate architecture by programming and testing vertical and horizontal (and every other direction) slices of the system [Cockburn04], [Monson-Haefel09]. This is not component-oriented development or layer-oriented development; rather, it is cross-component, cross-layer ‘vertical’ development that evolves a suitable skeleton in code . Nor is it prototyping; this is production-quality development in which an architectural foundation is implemented. The creation is a learning process that can include short cycles of architectural analysis, design workshops with agile modeling, and programming and refactoring by master-programmer architects. This tip is related to many subsequent tips.

The programming part of this is essentially what Hunt and Thomas have called tracer code development.

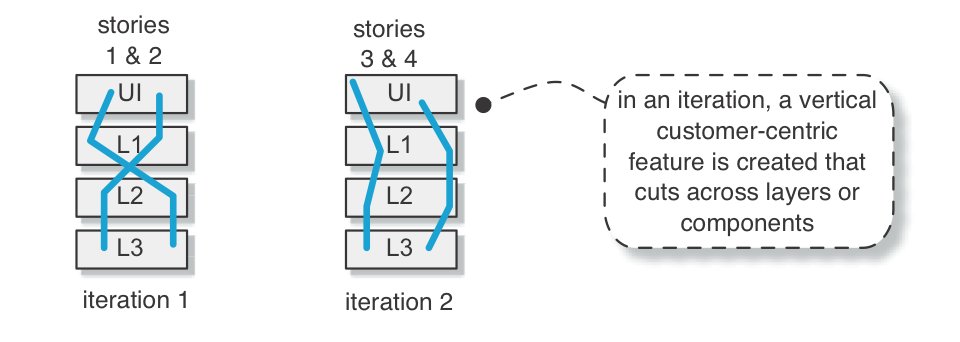

Incrementally build ‘vertical’ architectural slices of customer-centric features

I (Craig here) remember in 1995 at ObjectSpace we were developing a product for a customer. They wanted reporting and management of their business consultants and skills. For byzantine reasons beyond the scope of this story, we had to write our own object-relational (O-R) mapping subsystem in C++. So for the first three iterations (three weeks each, if I recall) the ‘talented’ developers developed the O-R component, focusing on creating that one subsystem first. Elegant lazy-materializing proxies with templatized smart pointers , and other geeky qualities. Then the customer visited for a demo of progress. The team was proud.

The customer was angry.

They had no idea what the point was of our subsystem, and it seemed to them we had spent nine weeks of their money doing nothing they cared about. They wanted reporting , they wanted consultant information management. They wanted to pull the plug.

The moral of this story–that we learned the hard way–is a classic agile guideline: Focus iteration goals on customer-centric features or activities, not on components or subsystems . Yet as will be seen in the following tip, there is an important design qualification to this.

In Scrum, this is what is meant by doing a complete Product Backlog item within the iteration. In the context of XP, this has been called story-based development . In the Unified Process (UP), it is called use-case driven development .

Although there is no ‘vertical’ in software, given the way software structure diagrams are usually depicted, one could say to implement ‘vertically’ across layers and components (UI, database, …) to fulfill the one-user story or scenario, evolve and discover the required architecture to support the user feature, and get feedback. Rather than fully developing ‘horizontal’ subsystems divorced from customer features, develop vertically across the layers and components to fulfill the feature, slowing building out horizontally the components as more customer-centric features are tackled.

These ‘vertical’ customer features are developed by the Scrum feature teams.

This can be summarized as Incrementally build, iteration by iteration, architectural slices that tend to be vertical-cross-layer rather than horizontal-within-layer, driven by architecturally significant customer features.

This last clause, driven by architecturally significant customer features , is discussed in the next tip…

Do customer-centric features with major architectural impact first

This tip is similar to some of the previous tips, but with a stronger emphasis on the risk-driven prioritization.

We were coaching a small-ish (100 person) product group in Berlin some years ago. One of the operation and control user stories had a concurrency scaling goal of 80 simultaneous sessions (all with high responsiveness). Do that early .

In Boehm’s spiral invariants model (of good architectural practices in large-scale development) the fifth invariant implies that early iterations aim toward the milestone named life cycle architecture. By this milestone the core architecture elements (both hardware and software) should be programmed and in place–proven through early integration and serious testing of production code rather than speculation or mere prototyping (though prototyping in addition to this goal is also good). This is very sensible advice.

Therefore, choose to do, in early iterations, customer-centric goals (user stories, use cases, activities, …) while at the same time choosing from a set of features that also have major architectural implications (for example, a feature with hard performance requirements or one that requires touching many components). Choose customer-centric features that by being implemented force people to discover and deal with major architectural issues early on. Not all customer features compel people to identify and resolve the major layers, components, communication themes, or performance issues. Ignore those features in early iterations and instead choose the hard ones.

This tip is an example of risk-driven development (a theme of the spiral invariants), in this case addressing two risks:

- business risk–of not aligning with what the client values

- technical risk–of not building a solid architecture

Both have to be addressed in early iterations. No false dichotomy.

Architects clarify by programming spike solutions

In a gargantuan 20 MLOC product with a host of people titled ‘architect,’ it is so tempting and safe for these good people to think, “Well, that’s a pretty big and messy system now, and it’s been 23 weeks since I did any programming. It is so much simpler for me to write a document explaining what I want changed in the architecture. Why not? I know what’s going on.” Avoid that temptation; leave your comfort zone. Rather, encourage master-programmer architects to first refine and discover ideas through programming a spike solution –exploratory programming that drives a thin vertical spike through components [Beck99]. Follow that, perhaps, by leading a design workshop with agile modeling that conveys the insights to other developers or by documenting the discoveries in an agile documentation workshop.

Don’t let architects hand off to ‘coders’

In large product development, this handoff is a common problem. Instead, move to a model of master-programmer architects, architects as pair programming mentors, architects as design workshop coaches, and so forth.

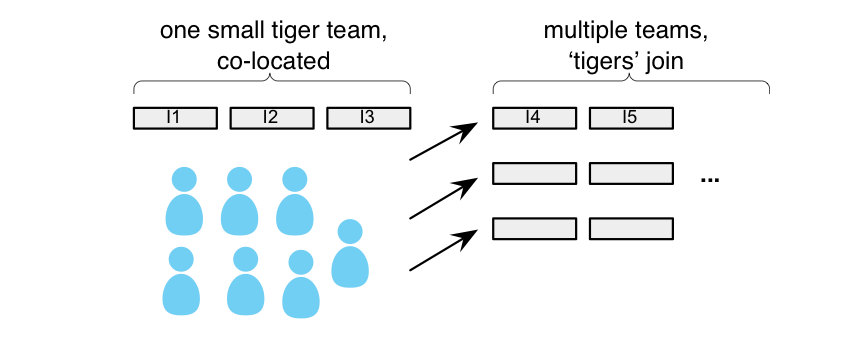

Tiger team conquers then divides

For the initial release for a new product or a major rewrite of core architecture, try starting the work with a co-located “tiger team” of great programmer-architects in one team room. Do not start off with a giant group. Keep it to a small tiger team until it hurts; they first program and conquer the key architecturally-significant features.

Repeating a quote (from page 1) on the 1950s large SAGE development, a senior project manager was asked about lessons learned:

He was then asked, “If you had it to do all over again, what would you do differently?” His answer was to “find the ten best people and write the entire thing themselves.” [Horowitz74]

Then, assuming it is starting to hurt (more people are needed; the feature velocity is much too low), explore ways that the tiger team members can divide to help in the formation of multiple teams.

Perhaps half the tiger team members disperse to join new feature teams. This may mean returning home to Bangalore after four months in Boston. Maybe four or five new people join the now-shrunk first team.

Any roaming tigers will play a technical leadership role and educate new team members in new teams on the core ideas, through pair programming and during design workshops.

Elssamadisy and Elshamy have cleverly coined this practice Divide After You Conquer .

We remember a horror story from a product group that did not apply this tip (we started coaching there during release-3): The first release was a disaster. What happened? It was a new product, implemented in C++. They took ‘experienced’ Powerpoint-architect ‘experts’ from a successful legacy product–who had never implemented a C++ or object-oriented (OO) system–to write architecture documents. Then 200 programmers started development from day one, distributed across two sites. Many had never worked with an OO language, so they were given a three-day course in C++. The product was two years late and during release-3 they were still fixing major quality issues and redesigning “the architecture.”

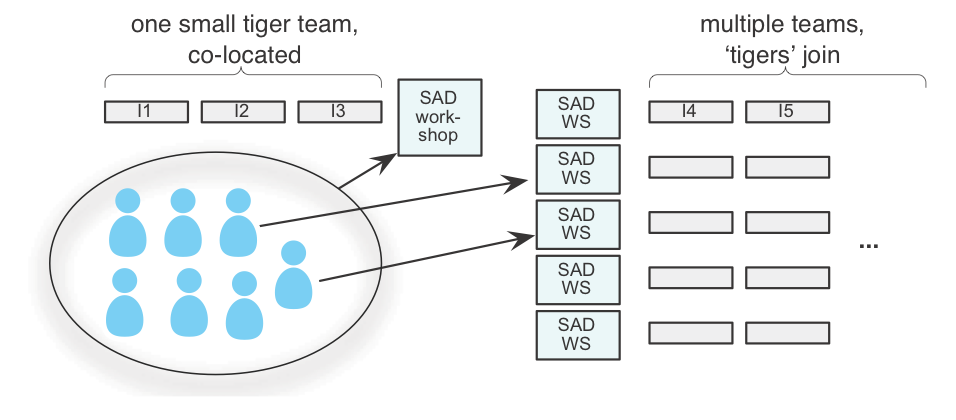

SAD workshops at end of “tiger phase”

A system architecture documentation (SAD) workshop may be useful at the end of the tiger team phase, to provide a learning aid for the new teams that will soon join (See a time to get SAD.). It may be useful to start the teams with a second SAD workshop, for education. Note that these practices try to reduce the lean wastes of handoff andinformation scatter . See subsequent experiments for more on SAD workshops and creating an agile SAD .

Back up “human infection” with an agile SAD workshop

The lean waste of document handoff is a major invariant in software development–handoff just does not work well. Indeed, design documents rarely even get read by hands-on developers. Therefore, a theme of threse tips has been to focus on educating developers through “human infection,” through careful and ongoing face-to-face coaching from manager-teachers who are up-to-date master-engineers, and from other technical leader-teachers. By ongoing–each iteration–participation in design workshops, system architecture documentation (SAD) workshops, pair programming, and code reviews, these technical leaders and master teachers ‘infect’ their colleagues with ever-broader and deeper understanding of the system design.

Yet, this agile advice could be mutated into another false dichotomy: human infection or documentation. Especially in large systems, try both. Emphasize leaders-are-teachers, while at the same time backing this up with a SAD. Plus, by creating or evolving a SAD in agile SAD workshops , the event itself–involving a medium-sized group, often with representatives from many teams–becomes another opportunity for teaching and learning.

A SAD workshop is different than an agile design workshop. How?

- Design workshops are done before doing real design–the source code. The output of the workshop is conversation, learning, and speculation–sketches on walls. For large-scale system speculation, multi-team design workshops apply. Design workshops–for one item or the overall system–are highly creative.

- SAD workshops are done after the implementation (for example, shortly after a release every six months). A SAD workshop looks backwards at the finished system, and describes it. It is not creative, but it is informative–as the participants learn more about the existing architecture, and generate ideas for improvement to consider in future multi-team design workshops.

For the content of a SAD, consider the N+1 view model and technical memos ; see the Documenting Architecture chapter in [Larman04a].

For recording the SAD, take digital photos of the N+1 view sketches on the whiteboards and store in them in a wiki. Also, type technical memos into wikipages.

Technical leaders teach during code reviews

Code reviews are customarily characterized as an event for identifying defects and are seldom done (it seems) by senior product architects. But the event can be used for education rather than just defect discovery–especially to help improve design skills and to maintain architectural integrity. A key lean principle is “Go See” or “go see at the place of the source of the problem and fix it there.” Architects or technical leaders who attempt to establish and maintain architectural integrity only through creating presentations or documents will not succeed well. But master-programmer architects, who regularly spend time doing code reviews (the “real place”) with developers, have a chance to educate others in these goals in the most concrete way, while also keeping close to the true design–the code. This tip supports the lean focus of seniors-as-teachers.

Don’t wait for approval reviews by experts

What’s wrong with this picture?

To start with, this increases the lean wastes of delay, handoff, and information scatter. There is also a lost opportunity for coaching and education: If the expert who received the document for review and approval is critical to ensure a good design, they should be at the early agile design workshops with the team, so that the original design is better, and so that they can teach the team to improve their speculative designs during original creation.

An external approver also forces an external process on the team; they are no longer fully in control of their work practices and improvement experiments.

At Nokia (where Bas used to work), they used to apply a traditional review/approval process: a document was inspected and approved (or not) after it was written. As common with handoff waste, there was a delay until it was reviewed, and feedback was indirect. Plus, if corrections were required, the cycles repeated.

To improve, they introduced a workshop technique called RaPiD7 [Kylmäkoski03]. The document was written and approved during one workshop with all the relevant stakeholders there so that there was no need for a separate inspection/approval cycle, and also to increase learning.

This experiment is not about stopping reviews or feedback; it is about changing the ways of work so that reviewing is a positive experience: value-adding, fast, and educational–rather than the traditional negative experience of delayed-approval processes.

Design/architecture community of practice

Communities of practice (CoP) are an organizational mechanism to create virtual groups for related concerns. The technical leaders or programmer-architects who are responsible for knowing and teaching the architectural vision are members of feature teams. If these technical leaders are scattered onto various teams, they have a need to regularly get together for many reasons, and to have a shared information space. They can form a CoP and share a CoP wiki space.

Show-and-tell during workshops

If related teams participate in a common design workshop, it is useful both for feedback and education for teams to visit other teams’ walls once or more, to hold “show and tell” sessions. This is also useful if one team (of seven people) decides to split into two sub-groups during the workshop and model different features in parallel. Group One is invited to the Group-Two wall to see and learn the design ideas, and help evolve them. And, vice versa.

Component mentors for architectural integrity when shared code ownership

Successfully moving from solo to shared code ownership supported by agile practices doesn’t happen overnight. The practice of component mentors can help. Super-fragile components (for which there is concern8) have a component mentor whose role is to teach others about the component ensures that the changes in it are skillful, and help remove the fragility. She is not the owner of the component; changes are made by feature team members. A novice person (or team) to the component asks the component mentor to teach him and help make changes, probably in design workshops and through pair programming. The mentor can also code-review all changes using a ‘diff’ tool that automatically sends her e-mail of changes. This role is somewhat similar to the committer role in open source development, but with the key distinction of not blocking commits from others; blocking would create massive bottlenecks and delay.9 They are teachers and component-improvers, not ‘gates.’ Component mentor are another example of the lean practices of regular mentoring from seniors and of increasing learning.

Component mailing lists

Another technique to supported shared code ownership is a mailing list (or other channel) for each delicate component. People working often on a component discuss refactoring, structure, bugs, code reviews, announce training, and so forth. Of course, anyone can join or leave a list according to need; any component mentors are long-term members.

Internal open source with teachers—for tools too

Agile development encourages shared code ownership. And feature teams imply working on all necessary code for a feature. In this sense, agile development in similar to an internal open-source model of development, but with the difference of even more collective code ownership and no committer ‘gates’ that create delay; rather, component mentors–if needed–help without blocking. As an agile coach, “internal open source, with some mentors” can be a useful way to explain the idea of collective code ownership, because most people know that various open-source models can work well.

Extend this to internal tools, not only shared components. Rather than “the team in Poland maintains our test tool,” experiment with an internal (or even public) shared code or open source model. Good developers master and evolve their tools; this model promotes that.

Configurable design for customization

Several of our clients have dug themselves into a rather difficult hole by creating a separate branch for each customization of their product for different clients. Those who have experienced this–especially in very large systems–know all-too-well that this increasingly becomes a configuration, maintenance, and testing pain as the years and number of branches grow.

Rather than branches, try configurable designs (for example, with meta-data or some pluggable architecture) that activates/includes (or not) specific components or features.

Use architectural and design patterns

Detailed architectural design for large systems is beyond the current scope, which emphasizes process-oriented design tips. But there is a wealth of well-written robust solutions in the design pattern community to help create an agile architecture. Get the books, learn and apply them (see Recommended Readings).

As a theme, patterns provide a protection at some variation point in the architecture, through indirection, meta-data, interfaces and polymorphism, and more. These techniques reduce dependencies and enable more, and faster, concurrent development in large products with many teams. Creating more knowledge faster and delivering value quicker are key goals in lean thinking.

The ninth agile principle emphasizes good design: Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility .

Promote a shared pattern vocabulary

If technical leaders consistently develop and communicate (both in words and how they name software components) with well-known patterns, they help establish shared-design understanding and perhaps more architectural integrity. This occurs in part through creating a shared vocabulary among developers. Patterns have official published names, such as Layers , MVC, MVP, Strategy , Broker , Service Locator , and so forth. These proper names can be used consistently in documentation, speech, and code–for example, an interface named RoutingStrategy . Although the prime value of patterns is reusing good design ideas, they can also establish a common vocabulary for your system’s design. When scaling to a system with 300 developers in many sites, that helps.

This tip seems obvious, but some technical leaders are not sensitive to the positive influence they could have as teachers . Creating shared vocabulary is a tool that skilled educators apply.

Technically Oriented Tips

Over the time that we have worked with large products, usually embedded systems, we have built up a list of common tips that could have reduced some of the pain and suffering we see and our clients feel. This section lists a few of these tips. An entire book could easily be written on this subject…

HTML-ize and hyperlink your entire source code, daily

With a small system one can navigate rapidly through all the source code simply loaded within your development tool. When there are 36,839 files and 15 MLOC, navigation is not easy. Use a free tool such as Doxygen (www.doxygen.org) to transform your source code into a set of HTML pages, in which all source code elements (functions, …) are hyperlinked. Doxygen (and similar tools) will also generate diagrams that reflect larger structures and groupings in your code base. Regenerate the pages daily. This is immensely useful for understanding and evolving a massive code base.

Use lots of stubs, plus dependency injection

Create stubs 10–or ‘fake’ code alternatives–for many things: classes, interfaces to other components, hardware, and so forth. Stubs are usually created with an alternative interface implementation or by subclassing the ‘real’ class in object-oriented designs, or with function pointers or alternate implementation files on a varying link path in C-based designs [Feathers04]; for example:

{% highlight java %}

interface PrinterMotor {

void start();

…

}

class CanonPrinterMotor implements PrinterMotor {

…

}

class PrinterMotorStub implements PrinterMotor {

…

}

{% endhighlight %}

If there is no interface (and even if there is), stubs can be created through subclassing and overriding relevant methods:

{% highlight java %}

class CanonPrinterMotor {

…

}

class PrinterMotorStub extends CanonPrinterMotor {

…

}

{% endhighlight %}

Further, provide a “back door” in many classes that makes it easy to inject a dependency to an alternative stub rather than the real object; for example, with constructor injection [Fowler04].

{% highlight java %}

class LaserPrinter {

private PrinterMotor motor = new CanonPrinterMotor(); // default …

public Printer( PrinterMotor alternativeMotor ) {

motor = alternativeMotor;

}

}

{% endhighlight %}

The combination of many stubs with many back doors for dependency injection opens up tremendous advantages: increased concurrent engineering, early integration with stubs when the real components are not available, testing with stubs, stubs that provide fast and well-known demo data. In the context of large product development, massive use of stubs is a key technique to work in parallel and go faster, reducing the lean waste of waiting.

Don’t use stubs to delay integration

Wonderful! Now that everyone has stubs you can delay integrating all the code for months or even years. Don’t even think about.

Test-driven development for a better architecture

TDD can help improve the architecture of a system. How?

When we are coaching, a frequent request is help for dealing with our client’s “inflexible architecture.” This most often boils down to problems in high coupling between components–a common problem in legacy code written without TDD because the original developer did not try to test the component in isolation.

On the other hand, when a developer creates a new component (such as a class) with TDD, or refactors a legacy component to be unit-testable, they must break the dependencies of that component so that it is testable in isolation . That requires designing (or refactoring) for dependency injection and increased use of mechanisms for flexibility: interfaces, polymorphism, design patterns, dependency injection frameworks, function pointers, and more.

In this way, TDD encourages lower coupling and simple, flexible configuration–qualities of a good architecture.

Use an OS abstraction layer

We work with two clients of similar large multi-MLOC embedded products. Client-A created a homegrown operating system (OS) and wrote the higher layers directly coupled to it. Client-B created an OS abstraction layer on top of their original OS (VxWorks)–a level of indirection for protection at that variation point. At some point, they both decided to move to a real-time Linux OS. Client-B finished the port in a couple of months; after some years, Client-A is still exploring. Agility through low coupling .

This tip is automatically satisfied if you are using Java or a similar platform. However, most of our embedded-product clients are using C and C++. In this case, try one of the existing open-source OS abstraction layers, such as Boost or the Apache Runtime Library.

Introduction to Interfaces and Interactions Tips

Defining and evolving interfaces between components and inter-component interaction are major issues in large-systems development. In fact, what Grady Booch11 has called “designing at the seams” [Booch96] is arguably the dominant architectural issue in big applications. Note also that the pain of ‘integration’ in multisite or super-large products is a reflection of interaction . When you are working with a 15 MLOC behemoth composed of 234 major components, each containing on average 64 KLOC, it is the interactions and interfaces that tend to dominate day-to-day overarching architectural concerns, not the design of any one module–or even what modules are present.

Interfaces –In this section, the notion of ‘interface’ includes

- interface as used in Java or C# (local or remote)

- operation signature (function name and parameters)

- web service interface (for example, with WSDL)

- and the like

Large systems are usually old; lots of C code is common, and the ‘interface’ to another component may be simply a function signature, such as debit( int, float ) . Another context for these tips is that in a 250-person product group, the client-programmer using a published API may be different than the service-programmer who implemented it years before.

Avoid big upfront interface design

An old–and unnecessary–strategy for the interface problem was “Before programming, define and freeze the interfaces between major components. Then, use a change-control process when interfaces need to evolve .” This is a decide-early push model of design; problems associated with it include

- delayed definition–owing to complexity and the many people involved

- lack of usage-based feedback

- incorrect interfaces (from lack of realistic feedback)

- slow change process

- extra conversion or adaptation code on both sides of an interface to deal with inevitable evolution when constrained by a frozen interface

There are workable alternatives to this unnecessary idea. The following tips offer lean thinking decide-as-late-as-possible alternatives.

Simplify interface change coordination with feature teams

A feature team is cross-component and changes all the code across all components necessary to complete a customer-centric feature. This reduces coordination problems related to interfaces because the same person or team works on both the calling and called side of the interface. In contrast, separate component teams increase the complexity of interface coordination.

Avoid freezing interfaces

There are times when a published API truly needs to be frozen. But challenge these decisions, keep things as unfrozen as possible, and experiment with techniques to support evolution of interfaces. Some techniques are suggested here and others in the Recommended Readings .

Wrap calls to remote components with proxies or adapters

Remote components–called via JMI, RPC, SOAP, message-oriented middleware (MOM), or a socket–are a guaranteed point at which people will want to inject a stub to allow testing in isolation, no longer talking to the remote element. Further, it is common that the remote communication mechanism (such as RPC versus MOM) will change.

Therefore, you want protection at this variation point in the architecture by always wrapping the calls to other remote components with objects and polymorphism, using the Proxy or Adapter design patterns [GHJV94].

Start with indirect interaction between major components, then replace as needed

Large systems are typically composed of hundreds of major components, and these may be local or remote to each other. We see common problems related to interaction between major components (such as subsystems) in big systems:

- dependency on knowing what major component is the receiver of a message or operation call

- dependency on knowing the communication mechanism, such as a direct function call, RPC, SOAP over HTTP, and so forth

- complex and repetitive communication failure handing

- inability to use pluggable features/components because of high-coupling problems

The following tip may help…

The computer scientist David Wheeler was famously quoted as saying, “Any problem in computer science can be solved with another layer of indirection.”

A resolution to the above issues is to use an indirect communication mechanism between major large components (such as subsystems), in contrast to something direct such as a Java RMI or SOAP call. This “indirect interaction” is deeper than just adding an adapter or proxy between components; it means using some form of indirect messaging system.

There are several options for indirect messaging between major large components. One robust choice is message-oriented middleware (MOM), such as JMS and MSMQ. Rich with options, supportive of pluggable architectures, MOM is worth a close look. Home-grown or open source lighter-weight “message bus” MOM solutions are another option. Doing inter-component communication with MOM provides a degree of freedom that enables lower coupling and more pluggable architectures. MOM solutions also offer built-in communication fault-tolerance and recovery features.

Actually, there was a second sentence in Wheeler’s quote that is less known; here is the whole thing:

Any problem in computer science can be solved with another layer of indirection. But that usually creates another problem.

Sometimes, “another problem” is a performance impact.

A potential MOM disadvantage is a performance drop. In this case, as with the weakly typed interfaces tip, you can start with a MOM solution to discover the “desire lines” of communication while ignoring the performance degradation. Then, as communication pathways stabilize and you discover performance hot spots, you replace slower MOM interactions with faster mechanisms such as the Java RMI. This is another example of pull design. MOM remains the default mechanism unless it is not performant for a case.

If this tip is combined with the tip to always use proxy or adapter objects for remote-component communication, then when the back-end mechanism is changed from MOM to RMI, the internal code is not affected–one simply needs to inject an alternative adapter.

Conclusion

Buildings are hard and static. Software is soft and dynamic. So, ‘architecture’ is far from an ideal metaphor for creating software; it can even promote the misunderstanding that there is some design other than the source code, and that the design is essentially frozen.

But the software design is continually evolving and emerging with every modification to the code by every programmer. The key question is: Will it emerge as a beautiful well-tended garden, or as a jungle of weeds?

The tips here encourage high-quality emergent design by a development culture of gardening and shorter and richer feedback cycles, rather than ‘architecting.’ And that requires great gardeners: master-programmer architects who actively code the architecture and who continually coach other programmers during pair programming and agile modeling design workshops.

For sustainable large-scale agile systems, it is vital for people to master design techniques for flexibility: design patterns, dependency injection, test-driven development, refactoring, and more. But without a culture of coaching-while-coding by technical leaders, these techniques will not be sticky or pervasive.

We suggest no false dichotomy between coding and modeling; the latter is valuable–especially in large-scale systems. In addition to a focus on code, agile modeling design workshops are a great, lightweight technique to quickly explore speculative designs and learn together. Perhaps the key ingredient is massive ‘whiteboard’ spaces, therefore, take over the walls!

Recommended Readings

- The site www.codingthearchitecture.com emphasizes the need for architects to be master hands-on active developers.

- Many of our clients have vast quantities of messy legacy code that is difficult to test in isolation and difficult to evolve. Michael Feather’s Working Effectively with Legacy Code is an important antidote, covering the techniques that allow developers to start designing a more agile architecture within their existing code base.

- A key element of technical agility is design patterns. Consider these texts: Design Patterns , Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture (five volumes), Applying UML and Patterns , and Pattern Languages of Program Design (five volumes).

- Two books by Bob Martin encourage a more agile architecture: Agile Development, Principles, Patterns and Practices and Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Craftsmanship.

- Two more useful quality-code-oriented books include Code Complete by Steve McConnell and Implementation Patterns by Kent Beck.

- Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests by Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce reinforces a culture of growing rather than specifying “the architecture.”

- Domain-Driven Design by Eric Evans encourages thoughtful iterative design, shared understanding, and a domain model that must be well-expressed in the code.

- The paper Agile Product Development explores the business value of product development and design agility, and how how development flexibility can be quantified.

Notes

- No false dichotomies: This example is not meant to suggest avoiding technical excellence or thoughtful design; it suggests design and architecture that is gracefully adaptable in response to learning.

- They are separate things when one is creating a physical object such as a hardware device; we refer to software architecture.

- The term “software architecture ” is not a ‘truth’; the name arose haphazardly by some people in a young field looking for analogies. Like all analogies (including ‘gardening’), it has strengths and weaknesses.

- Three-dimensional (3D) printing, in which complex objects are built from a 3D printer, is similar in this respect.

- For example, the brands Write-On Cling Sheets or Magic Chart.

- It is noteworthy that we know several people who used to–but no longer–work for UML CASE/MDD/MDA tool vendors, and none of them use those tools in their current development. It is also noteworthy that programmers at CASE/MDD/MDA tool vendor companies often do not use their own tool to develop their own tool!

- It may be useful to create design documents, but to reduce the waste of handoff a skillful means to discuss and understand its ideas is during a design workshop–at the walls.

- A typical reason for concern about delicate components is that the code is not clean, well refactored, and surrounded by many unit tests. The solution is to clean it up (“Stop and Fix”), after which a component mentor may not be necessary.

- But the roles are not identical. Guardians (or ‘stewards’) do more teaching and pair programming, and allow commits at any time. Committers also teach, but less so, and control the commit of code.

- Some incorrectly use the term mock when what is meant is a stub or, more broadly, a test double . Martin Fowler has addressed this in his online article Mocks Aren’t Stubs. In practice, stubs are far more common than mocks [Meszaros07].

- Software is a fast-changing field; thought leaders quickly become lost to a new generation. Do not miss studying the writings of Grady Booch, an OOD pioneer.